By John W. Whitehead

By John W. Whitehead

2/21/2011

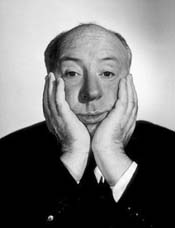

“Everything’s perverted in a different way, isn’t it?”—Alfred Hitchcock

Do you ever wonder why some of the greatest performers and directors of all time have never won an Oscar? It certainly has nothing to do with lack of talent. For example, the man considered the greatest director of all time, whose films have affected millions and changed the history of cinema, never received an Academy Award for best director.

In a career spanning half a century (1925-1976), Alfred Hitchcock completed 53 feature films—23 British and 30 in America after moving to Hollywood. Hitchcock is routinely and without doubt listed as the best film director of all time. His films are heralded as some of the most influential movies ever made—affecting the directing styles of other directors around the world who are now considered masters themselves.

Hitchcock received accolades and awards that, if piled together, would form a vast mountain. Only one award escaped him—an Oscar for best director.

As curious as this seems, it is not all that surprising. The Academy Awards have always been drenched in political wrangling where the factors of who and what film receives an award often seem inconsequential. After all, what does being a “sentimental favorite” have to do with judging talent? In the process, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences has missed some big ones—including, among others, the failure to award the best picture Oscar to Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane, now acknowledged as the best film ever made. One wonders how many great artists and their films are being overlooked by the Academy as it prepares to hand out another batch of gold-plated statuettes.

Hitchcock was a master of cinema. Many of his films are without equal. Rebecca is a gorgeous Gothic women’s picture; Notorious is a tragic love story; Under Capricorn, a rich account of emotional self-sacrifice; Strangers on a Train, a key exposition of the madman hero; Rear Window and Vertigo, superb commentaries on watching film; The Wrong Man, an exemplary study of chance and routine in conflict; North by Northwest, a brilliant view of a frivolous Cary Grant being sobered by feelings; Psycho, a scream of horror at the idea of madness; and The Birds, an audacious use of science fiction apocalypse to dramatize intimate emotional insecurity.

These are ten films that are masterly produced and demand endless viewing. Indeed, in my opinion, Vertigo may be the best film ever made. Incredibly, however, it did not receive an Oscar nomination for either best film or director.

Hitchcock not only created great films, he also raised some actors to mythic status. This is certainly the case with Cary Grant in Suspicion, Notorious and North by Northwest; James Stewart in Rear Window and Vertigo; Anthony Perkins in Psycho; Grace Kelly in Rear Window and To Catch A Thief; and Tippi Hedren in Marnie and The Birds.

Film was Hitchcock’s world. And his method was to lose himself in meticulous planning—so much so that the actual shooting of the film became a chore. In fact, Hitchcock was heard to say on numerous sets, “The actors are here. Now the fun is over.”

Hitchcock, writes film historian David Thomson, had “the style of an immense, premeditative artist—much like a Bach, a Proust, or a Rembrandt.” And he had an obsession with control, which characterized his methods of filmmaking: his preoccupation with a totally finalized and story-boarded script and his complete domination of actors and shooting conditions.

Hitchcock aimed his films at the audience. He used our impulses and fantasy lives, wove them through his plots and filmed his movies as if they were dreams. He was a man of moral seriousness who understood the modern condition of anxiety and fear. Hitchcock showed us the violent, psychotic fruits of our impulses. And in his films, Hitchcock’s characters shared their impulses with us.

Hitchcock was a dark genius. But like all of us, he was human. He felt fear, angst and a need for recognition.

Recognition of sorts finally came in 1968 when Hitchcock’s best work was behind him and he had partially withdrawn from working. His spirits were lightened somewhat when it was announced that the Academy would be awarding him the Irving G. Thalberg Memorial Award “for the most consistent high level of production achievement by an individual producer.” As Hitchcock might have rightly guessed, however, this was something of a consolation prize from the embarrassed Academy after years of slighting him. Although Hitchcock had been nominated five times for best director, he had been repeatedly denied the Oscar.

When Hitchcock’s name was announced at the Oscar ceremony, he slowly walked down the aisle amid a standing ovation. As the fanfare subsided, everyone awaited a witty, offbeat Alfred Hitchcock speech—the kind they knew him for from television and banquets. Stepping to the microphone, Hitchcock said “Thank you” with no expression, turned and slowly walked back to his seat.

Obviously, the brevity of Hitchcock’s remarks bespoke, some believed, a quiet, lightly-veiled contempt. And according to his friend, playwright Samuel Taylor, they were correct: “Hollywood never knew what a great artist he was. Under the proper circumstances, Hitch should have been nominated for every Director’s Guild award and every Oscar. The basic hypocrisy of Hollywood is that they don’t really believe film is art. Hitch knew all this.”

Constitutional attorney and author John W. Whitehead is founder and president of The Rutherford Institute. His new book The Freedom Wars (TRI Press) is available online at www.amazon.com.

Print This Post

Print This Post